There’s no arguing that just about everyone near and far these days has a taste for respite.

The ceaseless effects of the pandemic. The endless political maelstrom. Inflation. Wildfires and even traffic seem to have worn everyone down.

While you can’t eat your way to tranquility, most people feel they can and want to try.

Possibly the most uncomfortable the entire nation has been simultaneously for generations, maybe ever, the notion of comfort food alone is, well, comforting.

Sentinel staff writers reached out across the community, and the world, this week, seeking thoughts, recommendations and deliberations on how best, if at all, to eat your way to some definition of happiness.

Fried, mashed and under hot gravy aren’t for everyone. Read on and find out what these eight people you might know have to say about foods that can bring you personal calm in the shared storm.

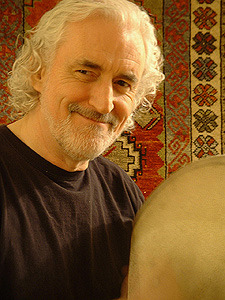

Black-eyed peas, turnip and mustard greens, ham hocks and other Southern delights filled the dinner table of Adrian Miller’s childhood. Born in Denver to a mother from Tennessee and a dad from Arkansas, the food historian and former Clinton White House adviser was steeped from a young age in the culinary tradition of soul food.

“That was my foundational cuisine,” he said, as he remembered working with his mother in the kitchen of their Aurora home. “I’m a big fish fan, and she used to make fried catfish with coleslaw and some kind of white bread, maybe some greens.”

Fish was a Friday treat in the Miller household. On holidays, the family would cook a savory, Southern-style barbecue spread of pork spare ribs, chicken and hot link sausages.

“The greatest expression was Thanksgiving, so you’d have the turkey, and then a bunch of soul food side dishes and desserts,” Miller said. “And on New Year’s Day, we always did greens.”

It wasn’t until law school that Miller said he started to develop a passion for cooking on his own. Later, after his stint as an adviser for the Clinton administration, he would pick up the book which he said sparked his interest in researching the origins of soul food — “Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History,” by John Egerton.

“The comprehensive history of black achievement in American cookery still waits to be written,” Egerton said in 1987 about the forgotten cultural contributions of America’s Black chefs.

“That book was 14 years old, and still no one had written that history,” Miller said. “From there, I started doing research and contacting people.”

Soul food wasn’t considered distinct from Southern cuisine as a whole prior to the 1960s, Miller said. But as Black migrants carried the traditions of Southern cooking with them out of the South, reimagining classic dishes with local ingredients, it became recognized as a unique piece of Black cultural heritage.

“When you’re a migrant, and you get to the new place, you try to recreate home,” Miller said. “Soul food is really about that dynamic of taking Southern food out of the south and recreating it in other places.”

Miller published his research as a book, “Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time,” which was awarded by the James Beard Foundation in 2014.

The phenomenon of people seeking comfort in cooking and familiar foods isn’t new — after 9/11, Miller said Southern cooking and barbecue “exploded in popularity.”

“Now, though, I think there’s just a lot more interest in food, period, and people are doing more cooking,” he said. “Some of that is cooking from TV. But I’m finding anecdotally, just talking to my friends who have kids, their kids are more interested in cooking.”

And while his mother died about six years ago, Miller said he still finds comfort over a plate of black-eyed peas, greens and smoked turkey, his own innovation — he said his mother would have used ham hocks.

“It reminds me of her,” he said. “All of those feelings are evoked. … It tastes good, and it’s delicious, but it also reminds me of home.”

— Max Levy, Sentinel Staff Writer

Settle in. Mick Bolger is talking this comfort cuisine thing through.

A musician, poet, artist, teacher and appreciator of the profound, he mulls memories, flavors and ideas around as he talks in the evening from his countryside home in Ireland, not far from the sea.

He moved there at the start of the pandemic from north Aurora, where he and his wife, Jean, had made a home and a life filled with Irish music, big ideas and a lot of laughs.

He considers the idea of using food to leverage tranquility or as a salve for what cruelty this turbulent life inflicts, some days worse than others. The thoughts and words roll off his tongue in a soothing Irish pace, his accent tamed by years of life in the United States.

He, and his band, Colcannon, became a force here, interpreting traditional Irish song, sung in lilty English or the more gruff Gaelic.

As far as food that brings just a serious sense of satisfaction, that was easy.

“I’d kill for a good smothered burrito,” Mick said. In Aurora, one of his favorite haunts was Real de Minas, where a tortilla wrapped around a boat-sized helping of moist rice, rich beans, and piquant chicken floated in a seat of gripping green chili.

The heat from the Colorado chilis, like that of the local Thai specialties, is “like a narcotic experience.” he said. Mouthfuls of pleasurable pain pumping endorphins through your veins and creating a sensual sweat at the top of your head.

Mick said his recent hopes for something like that in County Cork were dashed.

They’d made a rare venture out into the world of pandemic there to see Rembrant etchings at the Crawford Gallery and stumbled upon a Mexican restaurant.

It was ghastly, he said.

“The refried beans had raisins in them.”

Ewwww.

It sort of looked like a burrito, he said. Rather than green chili or salsa, it had some kind of tomato sauce on it that tasted like marinara sauce.

“I miss good Mexican food,” he said with a soft lament.

But as far as seeking out something incredibly satisfying to assuage some fear, some angst or some tribulation, he thinks that could be a very non-Irish notion.

“You’ve got to remember that Ireland was essentially a third-world country until the 1980s,” he said.

The idea of elevating food as a conditioner or operative seems, well, “gluttonous,” he said.

Not that he and all his fellow Irish friends and families don’t appreciate good stuff and a taste of the good life, but the experience is had for the moment, not so much carried years into the future and resurrected as a way to reel in comfort.

Except, maybe, for one thing. Christmas.

Christmas at the Bolger house wasn’t at all like that of his Irish neighbors. When he was just an infant, his father, an agricultural instructor in a program similar to Colorado’s cooperative extensions operated by universities, took a job in Nigeria in the 1950s, and the family went, too.

They were introduced, living in what would one day become Biafra, to Palm Oil Chop.

“It is extraordinary,” Mick said.

A centuries old tradition in West Africa, the dish is essentially a sumptuous stew made from chicken or sometimes beef. It packs a whopping punch of flavors that come from spices, chilis and local herbs, similar to a red Indian curry, but not.

Fried in red palm oil, the dish is served with rice and a variety of “side dishes.” These can range from anything like chopped fresh tomatoes or cucumbers to extravagant chutneys or nuts or dessicated coconut.

The magic, and Mick’s memory, hovers on trying different combinations of accoutrements on the rice with the stew.

“Did you try the apple with the nuts and coconut?” he and his siblings would marvel on Christmas Day as they spent hours working through the feast, sometimes with friends.

It was filling, fun and — memorable.

His sister to this day has “the curry” for Christmas every year, mixing up the sides to keep the experience traditional but contemporary.

He does, too.

Would he ever create the feast to fill a place in his head that needed his family or just remembering a good time?

Probably not.

He’s living in the moment right now. The moment sometimes takes him to a favorite haunt not far from his new home that sports what the Irish have perfected: fish and chips.

The fish, from just down the road at the edge of the bay, can’t be fresher. The batter boasts just the perfect level of caramel-colored crispy, salty crunch but stays ever so slightly tender against the firm, sweet fish. The chips aren’t the giant flourary misfits that the sad English and lost Americans seem to prefer. Nor are they the overcooked shoestring varieties the French fawn over.

Like so much in modern Ireland, they’re just right.

The Irish staple dinner doesn’t need to conjure fond memories when it’s so much more enjoyable to just make them.

— Dave Perry, Sentinel Staff Writer

For Harry Budisidharta, comfort food is what he remembers eating when he was young.

“When I go to one of the Asian supermarkets like H Mart, I usually fill up my shopping cart with snacks and junk food from my childhood,” he said. “It’s a terrible thing to have the appetite of a 9-year-old but a grown man’s budget.”

He loves flavored potato chips, particularly shrimp and squid. He also loves instant noodles, especially the Indomie brand.

“I ate those quite a bit as a kid and I love eating them now, especially during a cold snowstorm like this,” he said Tuesday as snow blanketed Aurora.

Fried chicken is also a favorite of his, whether it’s from Popeyes, KFC or a local joint.

As director of the Asian Pacific Development Center, Budisidharta works to empower the local Asian American and Pacific Islander community. He praises Aurora for having one of the best, if not the best, selections of Asian restaurants in Colorado. Much of that is due to the significant number of immigrants and refugees living in the city, but he also credits the city council and chamber of commerce for their work bringing restaurants in.

The pandemic has not been easy on mom-and-pop restaurants, he said, many of which had a harder time getting relief and staying open than large chains.

“I think it’s turning around now, but I’m sure if you ask they will say it’s still a struggle for them,” Budisidharta said.

Some of his personal favorite restaurants in the city are Dae Gee Korean BBQ, Katsu Ramen and Angry Chicken, all of which are located in the 1900 block of South Havana Street.

“That’s a very deadly shopping complex for me,” he said.

— Carina Julig, Sentinel Staff Writer

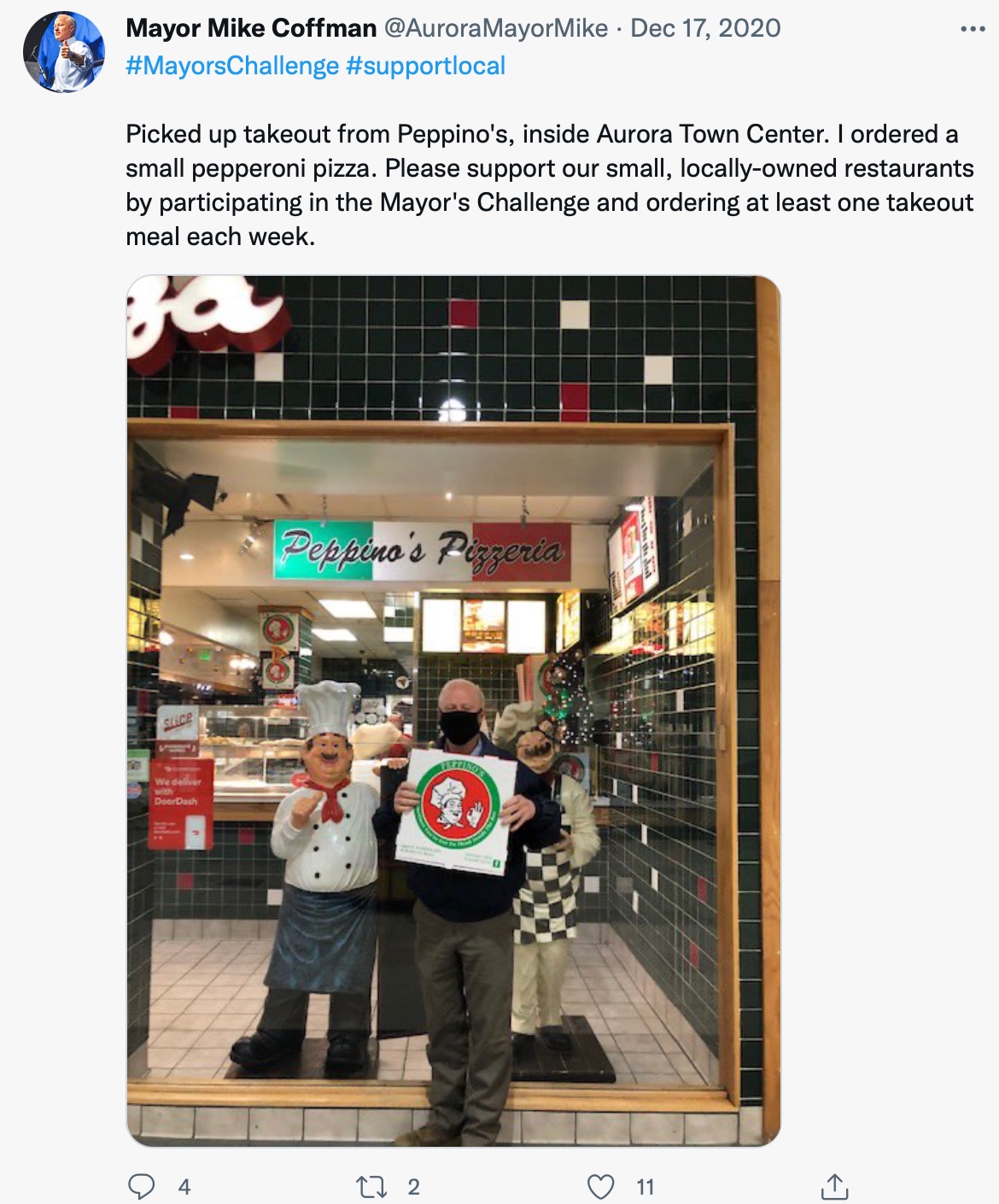

Oftentimes, comfort foods are a thing of necessity, a way to salvage some sort of normalcy during tough times. That was the case for Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, though it came about differently for him than most others.

As the virus tore through communities and restaurants were forced to close their dining rooms, Coffman took to takeout orders and his Twitter account to offer a solution: Patronize one local restaurant each week to help them stay afloat.

The ask came to be known as the “Mayor’s Challenge” and each week Coffman would try a new dish or two from one of Aurora’s vast array of eateries.

Over the course of several months, Coffman took his weekly challenge seriously, documenting his tour of local restaurants. One week the pork souvlaki plate with a Greek salad from the Athenian, a longtime Aurora establishment. Another, the baby corn Manchurian and grilled tofu tikka masala at The Madras Cafe, a small vegetarian Indian restaurant.

“The food was amazing and reminded me of when I studied at Vaishnav College in Madras, India (the city has been renamed Chenai) so many years ago under the University of Colorado’s study abroad program in 1976,” Coffman wrote on social media.

Try as he might, some local restaurants weren’t able to weather the storm.

“The sad part of the pandemic was that my two most favorite comfort food places have since permanently closed,” Coffman said.

Neither Sweet Tomatoes nor Mr. Panda Super Buffet is in business any longer. Both fit that comfort food spot for the mayor.

The Mayor’s Challenge led Coffman all over Aurora city limits. He was snapping photos with cafe owners, posting menus and encouraging locals to follow his lead. No two weeks seemed to be the same, though some meals have stuck with him almost two years later.

The vegetable samosas, garlic naan, tandoori chicken, and chai at Star of India on South Parker Road are now part of Coffman’s regular rotation, he said.

— Kara Mason, Sentinel Staff Writer

Kartoffelpuffer, bauern schnitzel and kuchen are on the menu at Create Cooking School’s sold out German comfort foods class later this month.

“Right now those heavier dishes are so popular. We are doing way more than we were before. The pattern is definitely there,” said AJ Winn-McClain, the school’s head chef instructor. “We just added a bunch of new classes, and most of them are geared toward those old comforts. People just love them.”

Oftentimes, people flock to classes at Create, located in Stanley Marketplace, for a little taste of something familiar, even if they’re just learning to make it for the first time.

It may be to make a red sauce that their Italian grandma made when they were growing up, or the smell of street food in Thailand from a previous vacation. Winn-McClain said he often hears comments from students during those classes that the dish takes them back to an old memory.

“That doesn’t really happen so much with our American food dishes,” he said.

Food memories can be powerful. Psychologists believe it’s because they involve all five senses and that food is good at reinforcing feelings. It isn’t so much about the red sauce itself as it is about remembering your grandmother’s kitchen: the sounds of old dishes clinking, the smell of fresh herbs and how good it felt to be there with somebody you loved so much.

It was this same kind of relationship with food that steered Winn-McClain to a career as a classically-trained chef. As a young boy, he would man the grill during branding parties at his family cattle ranch.

“We’d brand hundreds and hundreds of cattle. We’d be out grilling all day long,” he said. “I was just always kind of drawn to that kitchen side of things.”

A ranch is an easy place to learn to love food. Winn-McClain’s grandmother was an avid baker and his father loved to make fried chicken and schnitzel. “I definitely grew up around those comfort foods,” he said with a laugh.

Winn-McClain has noticed that more and more students have been commenting that they’ve picked up cooking during the pandemic, and so a class can be a great place to build skills or perfect a dish, even if it’s one they’re trying to recreate from their past.

The key is to not be afraid of failure, he said. That can be an intimidating part of cooking and revisiting old memories through food, but the first pancake theory — which goes that the first pancake is always a trial and usually a loss because you’re just getting used to the whole process again — applies to most all cooking.

“You are welcome to screw it up,” Winn-McClain said. “Being comfortable with failure is important. You know our grandmothers failed back in the day… imagine how many setbacks they had before they got that recipe exactly right.”

— Kara Mason, Sentinel Staff Writer

Comfort can be a complicated concept to manage.

You’d expect that kind of thinking from a poet who pushes around ideas to the edge of overthinking.

Jovan Mays is Aurora’s emeritus poet laureate. For the past few years, he’s been working with Aurora Public Schools students on helping them refine their own stories in a variety of media.

Jovan is a master at reflecting on his own lot.

On the philosophy of soothing some unrequited longing through gustatory indulgence, that didn’t go so well for him as a child.

Jovan moved at an early age from his first home in Denver’s Park Hill to Aurora.

“My dad worked for Rainbow Bread my entire life,” Jovan said. Family frills were few and rarely appeared as typical childhood favorites like soda pop, fabulous cereals, frozen treats and just about everything that takes up air time during Saturday morning cartoon shows.

“My family just didn’t really eat from the middle aisles of the grocery store,” he said.

So when one of his new friends in his Aurora neighborhood introduced him to the concept of “The Second Fridge,” he was intrigued.

These were Aurora families that had customary refrigerators filled with mayonnaise, broccoli, jelly, bacon, milk and lots of leftovers. But the “Second Fridge” in the garage? This was golden childhood bouillon.

His friend’s gold mine in a garage was filled with every kind of soda pop, endless varieties of ice cream treats and frozen concoction that most children are groomed to understand as comfort food.

The welcoming family of his new friend made sure he knew “this is all yours” and to feel free to indulge in whatever he wanted.

He wanted.

And he waited until after midnight. While everyone was asleep, he went back out to the garage and plowed through cream sodas, Otter Pops, Nestle Drumsticks and yogurt amazements.

“I ate myself sick at his house by accident,” Jovan recalled.

Lesson learned.

When it comes to foods promising comfort, be careful what you wish for.

Real comfort came in the kitchen of his own family home, from a cast iron skillet.

On exceptional occasions, his dad would bring home Jovan’s coveted favorite: chicken drumsticks.

The resulting home-fried chicken legs were only half of the treat. The extravaganza seemed to a little boy a long, pleasurable time in the making.

“It was always such a process,” Jovan said. Dishes for the egg wash, the flour dredge and maybe some spiced bread crumbs. There was the heavy, black skillet sharply contrasting with the Harvest Gold kitchen range, a source of modern appliance pride for his mom.

“I could barely reach the counter,” he said. But he was alongside his dad, captured with him in the kitchen, as the legs were bathed then dredged and then laid into a ferocious pool of snapping oil.

The experience was pure synesthesia, he said. A heady swirl of fragrant crust, angry oil and his dad propelling the legs to the finish line on the kitchen table.

Sometimes there was mac and cheese, On even rarer occasions, homemade collard greens.

The drumstick feasts were so rare and coveted that as a boy, he thought the chicken legs must be extravagantly pricey like prime steaks. As it turned out, the cost was his busy dad’s time, luxuriating over home-fried chicken.

Similarly, standing Sunday breakfasts were also part of his family’s food for comfort ritual. There were either pancakes or crispy potatoes, made perfect in the bacon grease, fried eggs and buttery toast with his mom. Those often ended in another part of the ritual, a trip to the pet fish store, as if it were a visit to a grand, mile-high aquarium just to ogle the marine oddities.

Thinking back on it, Jovan realized that comfort food tastes mostly like delectable family time. It was something he never tired of nor was able to overindulge in.

— Dave Perry, Sentinel Staff Writer

Food is near and dear to Denver Post journalist and Aurora resident Joe Nguyen’s heart.

He’s competed in some gut-busting competitive eating contests — including one in Downtown Denver in 2011 that included Nathan’s Hot Dog eating champion Joey Chestnut and several that involved eating a gallon of ice cream as fast as possible — and his affinity for Chipotle burritos in his formative years is legendary, but his comfort food is pho.

Nguyen is part of a large Vietnamese family and the country’s traditional soup dish is part of him in many ways.

As a child, the now thirtysomething remembers opening the door to his house after church every Sunday with the “fragrant aromas” of the broth that had simmered on the stove while the family was gone and it still resonates to this day. To find the best pho, Nguyen’s gone on a quest around the metro area and virtually anywhere he visits in search of the best-tasting version of the broth, which has subtle regional differences everywhere in Vietnam and in restaurants as well.

But nothing can match the home recipe handed down from his late mother, which he makes once every two or three months now.

“It’s basically the same recipe my mom used to make,” Nguyen said. “She taught it to me after she got cancer so it definitely holds more meaning for me.”

Nguyen often freezes his homemade batches and can heat them quickly, add meat and rice noodles and have a quick, yet nostalgic meal just about any time.

— Courtney Oakes, Sentinel Staff Writer

Like so many, comfort food evokes childhood for Hannah Cho, owner of Shin Myung Gwan Korean BBQ on Havana Street.

“It’s like my mama’s food,” she said.

She’s a particular fan of soup, which her mother cooked for her growing up, especially during cold weather.

“On a cold day like today when it’s freezing outside, Korean people, we love to have soup,” she said. “I grew up with tofu soup, that’s one of the foods that I eat a lot.”

Cho’s restaurant will celebrate its five-year anniversary this month. She didn’t start out in the restaurant industry — for 10 years she worked as a banker, and then after deciding she needed a career change became an investor.

Her friend Seong Nam Park — “I call her sister because we became like family in the U.S.” — worked at a Korean restaurant on Havana Street and would cook for Cho often.

Eventually the restaurant went on the market and Park encouraged Cho to invest so they could go into business together. Because it was at a good location next to Aurora’s H Mart and she trusted Park’s culinary skills, Cho took her up on it.

They’ve had ups and downs, especially during the pandemic, but so far have pulled through.

After the pandemic they changed their hours from 4 p.m. until midnight, which Cho said has boosted business by catching a lot of late night customers. (Who wouldn’t say no to short ribs or pancakes after a late night out?)

“We are happy that we made it,” she said.

One of her favorite things they offer is galbi, a dish of marinated short ribs. She likes to pair it with spicy tofu soup.

— Carina Julig, Sentinel Staff Writer